Deborah Orr: (who writes forthe Independent) A toxic legacy in a land the world would prefer to forget

Deborah Orr: (who writes forthe Independent) A toxic legacy in a land the world would prefer to forget

It isn't often that Kyrgyzstan (Pop 5.4 Mn) has a moment in the international spotlight, even though the country is home to the genetic parent of all the apples of the planet. But this week, one of the poorest and least visible nations on the planet had 15 seconds of fame.

The Kyrgyzstan president, Kurmanbek Bakiyev, announced that his country did not intend to renew America's lease on the Manas air base, which has strategic importance because of its proximity to Afghanistan. Russia has offered to give the Kyrgyzstan government a $300m, 40-year loan at 0.75 per cent, and to write off $180m in accumulated debt, but only if Kyrgyzstan sacrifices the $63m it has been receiving from the US for the base.

It's scandalous that the country should be quite so vulnerable to financial manipulation. It is hardly surprising. Since the collapse of the Soviet Union, Kyrgyzstan, like so many other post-Soviet countries, has been left to fend for itself.

When Vincent O'Brien, a lecturer in public health at the University of Cumbria, first went to the country's capital, Bishkek, in 2002, at the invitation of the State Medical School, he was shocked to find that this national institution had no paper, no electricity, no heating in temperatures of minus 20C, and no toilet facilities to speak of. The director of the centre for health research was on $30 a month. "I couldn't understand how people survived at all," he says, "And I had only met people from the universities."

After the Russian withdrawal, the country's medical infrastructure had been left in ruins. There was no cash to sustain the USSR's centralised "science-based" model, so Kyrgyzis wanted to develop a more socially oriented healthcare system. They'd acquired a small grant from the EU and approached O'Brien to help them do this.

Impressed by their determination and intellectual resourcefulness, in the face of difficulties that to him seemed almost insurmountable, O'Brien set about working with the Kyrgyzi academics. After a two-year development period, they had introduced three new degree courses, specialising in public health, and relying heavily on video film-making as a means of education. O'Brien had also formed a strong bond with the Kyrgyzis he'd worked with, and he and his family decided that they wanted to maintain the link. Since then, in his own time with his own money, O'Brien has travelled over much of the country. What he has found, to his distress, is that one of the last nomadic cultures in the world is painfully dying.

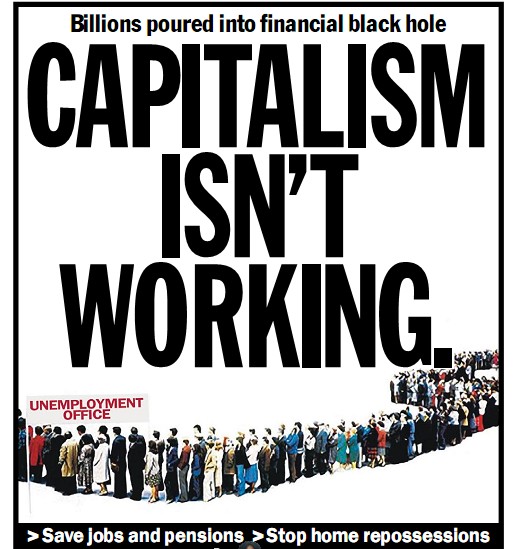

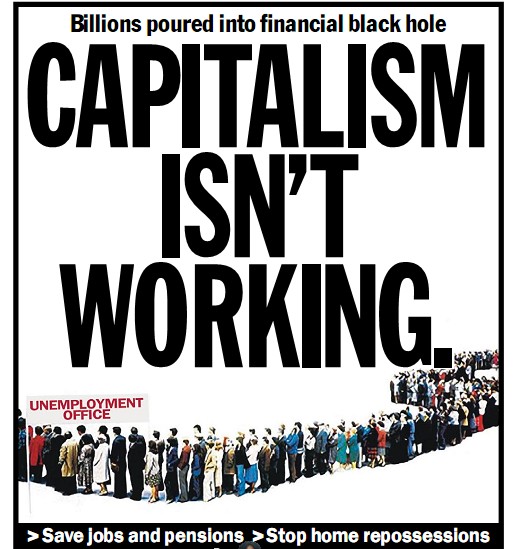

In some respects, O'Brien says, the rural people are better off than the city people. His Kyrgyzi friends work for a government that is barely paying them, and is unable to provide resources. Graduates in Kyrgyzstan rarely now work for the government, because it is considered the worst employer. Graduates often do not use their skills at all, in fact, because unemployment rates in the cities are way beyond 50 per cent. In the cities, full of beggars and hawkers, you have to have a job to manage. In the country, the ownership of land and animals ensures survival, in the short term at least.

Before the Soviets came, the people had been fully nomadic, and the land owned by no one. After collectivisation, it was owned by everyone, which proved to be quite a different thing, psychologically. In the 1990s, it had been parcelled off, with the biggest and best bits going to those closest to the Communist Party.

Those in receipt of land were rarely the shepherds who actually knew how to look after the animals, says O'Brien. Overgrazing had become common in the Soviet period, but back then imported feed had masked the problem. Now, the animals are weak with hunger, and falling ill with brucellosis, cowpox and anthrax, all of which can be, and are, passed on to the human population. There are no vets, because without land and animals you cannot subsist in the rural areas, so virtually no specialist skilled worker operates there any more at all.

Nevertheless, a tiny proportion of Kyrgyzis grow rich – they are considered to be "gangsters, politicians and their friends". Their money, it is suspected, is connected to the drug trade through Tajikistan. Some of the young people – in a country that is Muslim in the way that England is C of E – are looking to Islam in disgust at the social decay. The new buildings in the villages are always mosques, built with Saudi money.

What O'Brien sees is a people willing to work hard at solving their problems, but in need of some support. What most Westerners see is a US-Russian wrangle over an air base. Then we all wonder how a place gets to be a "failed state".

O'Brien has written ;

Adapting to Cultural and Environmental Change in Remote Herder Communities. Ak Terek

Foundation, Kyrgyzstan. Christensen Fund, USA. Kyrgyz State Medical Academy.

Using participatory photography and video for health and community development in Brazil

and Kyrgyzstan University of Cumbria, Kyrgyz State Medical Academy, Viramundo Brazil.